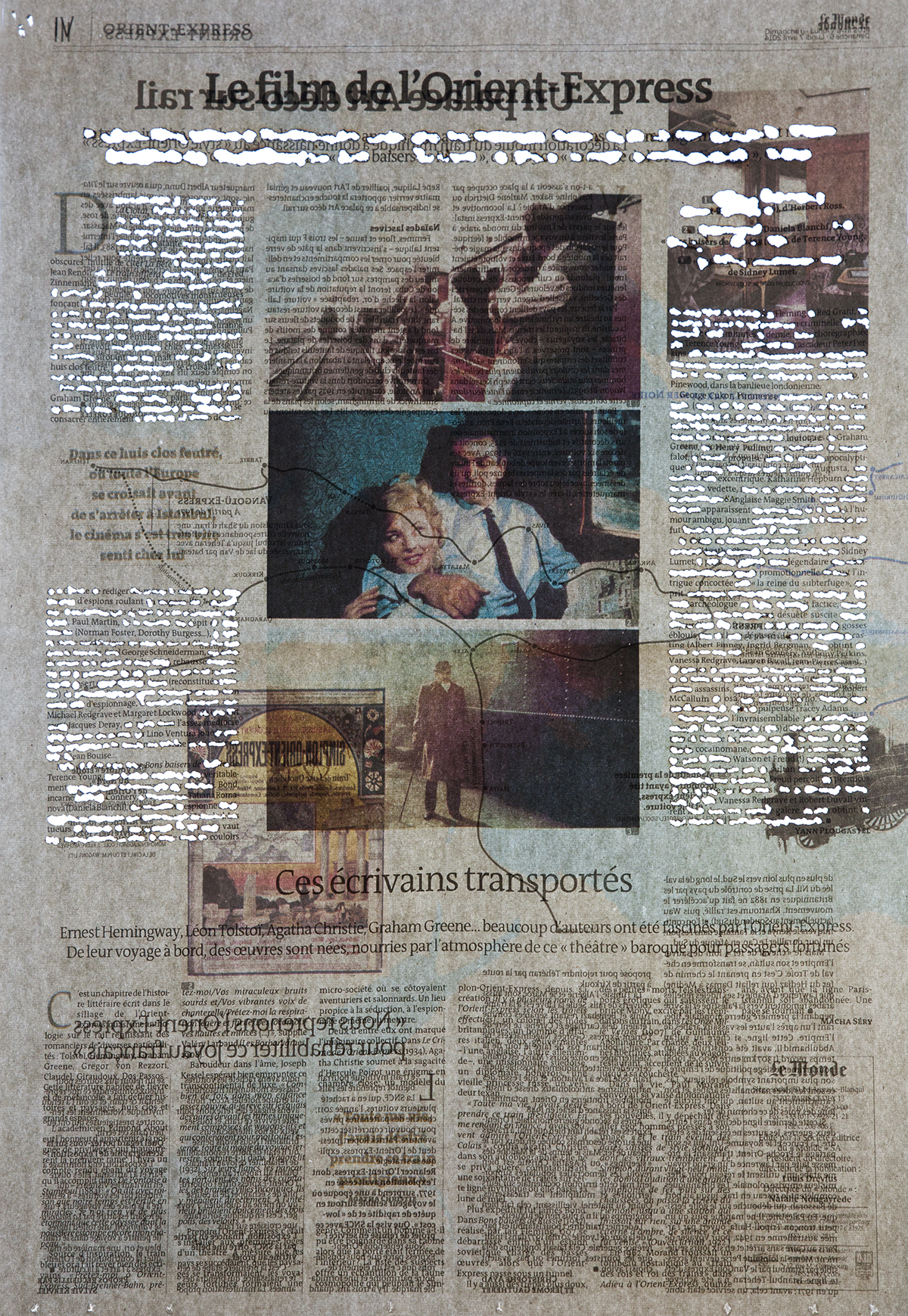

Le monde

FOAM Magazine#60

Glyphs, the Images and Text Issue.

09.2021

FOAM Magazine#60

Glyphs, the Images and Text Issue.

09.2021

Text on japanese artist Mana Kikuta’s work Le monde. The series both accompanied and embodied her adjustement to a new land and a new language through playing with the words on Le Monde newspaper.

Writing.